Tomb of the Unknowns Turns 100. The Shameful Story of How We Long Forgot Our Fallen Soldiers

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Is a National Treasure. What We Did Before Is a National Embarrassment.

Welcome to The Nonlinear Life. In case you missed it, read my introductory post.

Every Friday on The Nonlinear Life we talk about life as we live it today. We explore the urgent and emotional issues at the nexus of family, health, work, and meaning. We call it This Life.

---

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier turned 100 this week. Arlington National Cemetery celebrated by allowing visitors for the first time in a century to walk directly onto Unknown Soldier Plaza, hallowed ground usually reserved for sentinels of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment. Veterans and families lined up in throngs to pay tribute to the three soldiers from America’s 20th-century wars buried in that spot.

The original unknown soldier in front of Congress

This anniversary recalls the cold, rainy afternoon on November 9, 1921, when the USS Olympia docked at the Washington Navy Yard carrying the remains of an unknown doughboy from World War I. Gen. John J. Pershing, who had led American troops, stood bundled against the wind. The unknown soldier was buried two days later in Arlington National Cemetery in the recently constructed Tomb of the Unknowns. President Warren Harding attended.

(You can see an extraordinary film of those events here, courtesy of the National Archives.)

But while the Tomb of the Unknowns has become a well-deserved shrine at the heart of the American soul, this anniversary also allows us to revisit a forgotten, more shameful part of our past and ask two rather obvious questions: Why did it take so long to build such a memorial? And what did we do with unknown soldiers for the first 150 years of our history?

The answers to those questions allow me to bring up one of my Top 5 favorite history of books of all time, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, by Drew Gilpin Faust, the former president of Harvard. As someone steeped both in the history of the South and the rich literature on death and dying, I learned more from this monumental book than I can possibly convey. As Newsweek said at the time, “This Republic of Suffering is one of those groundbreaking histories in which a crucial piece of the past, previously overlooked or misunderstood, suddenly clicks into focus.”

National Book Award finalist, THIS REPUBLIC OF SUFFERING: Death and the America Civil War

Faust uses a host of letters, diaries, poetry, and song to show how the Civil War transformed America’s attitudes toward death. With 600,000 dead, the war revolutionized the end of life in ways we now take for granted—including introducing embalming, letters to the bereaved, and the notion of “a good death,” a pain-free, prayerful passing.

As Faust says, “We still live in the world of the dead the Civil War created.”

She devotes an entire chapter to the way the Civil War invented the notion of unknown soldiers. Here’s the opening of Chapter 4, called NAMING:

Men thrown by the hundreds into burial trenches; soldiers stripped of every identifying object before being abandoned on the field; bloated corpses hurried into hastily dug graves; nameless victims of dysentery or typhoid interred beside military hospitals; men blown to pieces by artillery shells; bodies hidden by woods or ravines, left to the depredations of hogs or wolves or time: the disposition of the Civil War dead made an accurate accounting of the fallen impossible. In the absence of arrangements for interring and recording overwhelming numbers, hundreds of thousands of men—more than 40 percent of deceased Yankees and a far greater proportion of Confederates—perished without names, identified only, as Walt Whitman put it, “by the significant word Unknown.

To Americans today, this situation seems unimaginable. The U.S. spends $140 million a year in an effort to find the 88,000 individuals still missing from the wars of the twentieth century. The obligation of the state to its soldiers is unquestioned.

Yet, that question had never been asked before the Civil War. Certainly, in 1861, neither the Union nor the Confederate armies thought it was their responsibility. What changed was not just the breathtaking numbers of soldiers who died but the tireless commitment of the living to identify and honor them.

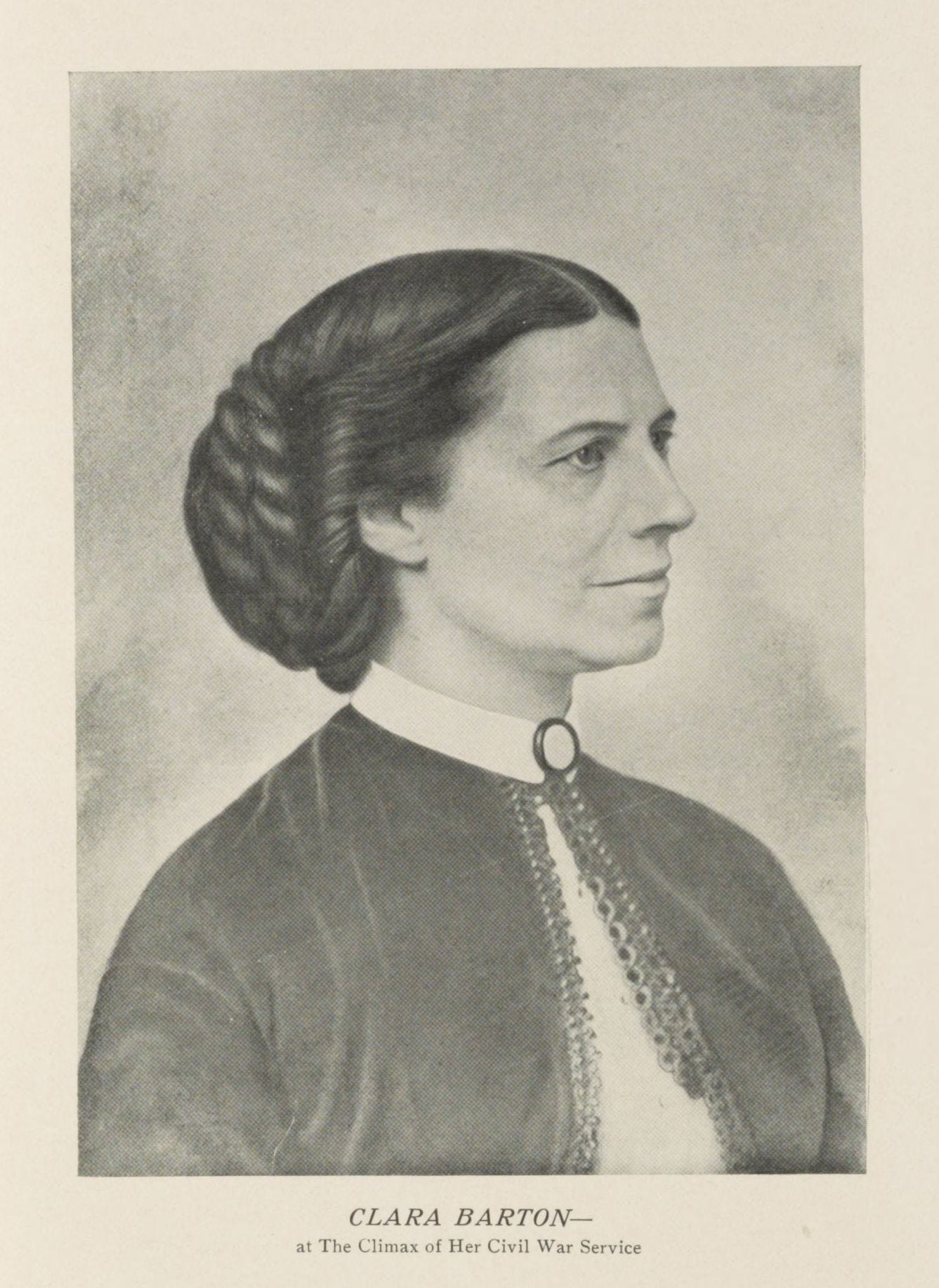

With the armies themselves doing so little, it was charitable groups, religious organizations, and loved ones who worked to fill the void left by government inaction. Identification was made from diaries, hymnals, or letters from home that the soldiers commonly stored in their breast pockets. Clara Barton became famous in part for her role in notifying families of their loved ones’ final days.

Clara Barton, American nurse who founded the Red Cross

Faust shares that after Sherman reached my hometown of Savannah, Georgia, in December 1864, delegates of the Christian commission who had been following his troops across the state rented rooms and installed 50 writing desks, where they produced 300 letters to relatives every day.

Where charity ended, capitalism entered. In the North, for-profit entrepreneurs popped up to hunt down remains for a fee. “In return for their efforts in locating men,” Faust writes, “they would claim a share of the deceased’s back pay or the widow’s pension.”

Members of Christian charity groups working to identify unknown soldiers

Unknown soldiers were not revered; they were profiteered off of.

After the Civil War, the U.S. government changed its policy—but only somewhat. During World War I, bodies were interred in whatever location they died. After the war, families were given a choice: leaving their fallen buried abroad or having them sent home. As anthropologist Sarah Wagner explains in her book What Remains, which won the 2020 Turner Prize, some families said the remains should stay in Europe as a signal of America’s commitment, but 70 percent of families chose to have them sent home.

The thousands of war dead in World War II who remained unidentified were buried in fourteen national cemeteries worldwide.

The Korean War marked the first time in which remains were returned home during the conflict itself. This decision followed a brouhaha in which a general received preferential treatment. Bodies were sent first to Japan for identification, then home. Historian Kurt Piehler explains that racism is one reason Americans did not want their loved ones’ remains to be interred permanently in Asia.

By Vietnam, the practice of immediate repatriation became permanent. Leave no man behind emerged as both a political and a cultural rallying cry. The peace accords of 1973 include a specific reference to help identify those missing in action. The continued presence of MIA flags across the United States shows how far the country has come: Tombs of unknown soldiers are no longer enough.

Every body must be identified and found.

Which brings us to the ultimate irony of this anniversary: Military observers now believe that with advances in forensics, no solder may go unknown again. The number of the tomb’s honorees will forever be fixed in stone.

☀

Thanks for reading The Nonlinear Life. Please help us grow the community by subscribing, sharing, and commenting below. Also, you can learn more about me, read my introductory post, or scroll through my other posts.

You might enjoy reading these posts:

What the World Series Taught Us About Men. They Love Pearls!

Or these books: Life Is in the Transitions, The Secrets of Happy Families, and Council of Dads.

Or, you can contact me directly.