This American Skier Won 5 Gold Medals. He Can't Use His Legs.

How a Mediocre College Skier Became One of the World’s Most Decorated Paralympians

Thanks for reading The Nonlinear Life, a newsletter about navigating life's ups and downs. We're all going through transitions, let's master them together. Every Monday and Thursday we explore family, health, work, and meaning, with the occasional dad joke and dose of inspiration. If you're new around here, read my introductory post, learn about me, or check out our archives.

---

In honor of the start of the Winter Olympics, this special edition continues our occasional series featuring a portrait of a nonlinear life well-lived, from the 400 life story interviews I’ve conducted since 2017. This interview was conducted in 2019 and is one one of many featured in my most recent book, Life Is in the Transitions.

“Skiing was always part of my life,” says Chris Waddell.

Born in Methuen, Connecticut, Chris started ski racing at six. “By thirteen, I was the best in the region. By fourteen, I went more than a year without finishing a race; I fell every single time. By fifteen, I was ready to quit.”

Chris didn’t quit. Instead, he built up his skills and joined the Middlebury College ski team. “I had a detour and was ready to prove myself again.”

But he struggled. “I kept thinking, I’m not good enough. Who the hell are you?”

By the middle of his sophomore year, Chris was feeling confident again. He was ready to return from winter break and make the team again. Then, the unthinkable.

“It was the 19th of December. I woke up at home. I was exhausted. My ex-girlfriend had dropped off a present the night before. My brother suggested we go for a run.”

On his third run, Chris fell. He had tumbled many times before, but this time felt different.

“My ski popped up, and I fell in the middle of the trail. I didn’t hit anything, but I broke two vertebrae and damaged my spinal cord. I might have said, ‘Oh no, I’m paralyzed now,’ but I don’t remember. It’s certainly what I was thinking.”

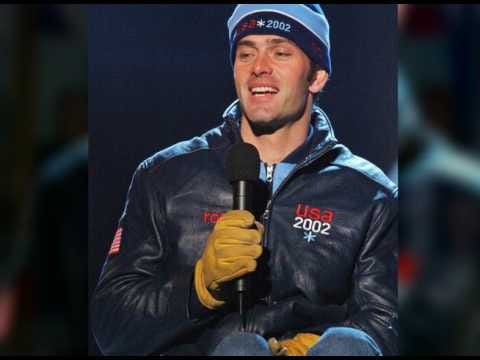

Chris Waddell

Chris lost the use of his legs but could still move his arms. He returned to school a month later in a modified dorm room. “I was able to dress myself. I dropped from 175 pounds to 125 pounds. And I was terribly depressed.”

The following summer he went to a rehab facility, determined to walk again.

A central part of absorbing of major destabilizing life event, what I call a lifequake, is learning to adjust the basic understanding of who you are and what you can do. A key part of that process is shedding. My research for analyzing hundreds of stories like Chris's show that people shed mindsets, habits, and routines in their most challenging moments. Chris, for example, had to shed his dreams of making the Middlebury ski team.

A big reason we shed, though, is to make room for what comes next: astonishing acts of creativity. At the bottom of our lives, we dance, cook, garden, take up ukulele.

In Chris’s case, his creativity took an unexpected turn. Just as he was confronting the reality of his injury, his rehab facility decided to put on a pop-up play. Chris was tapped for the lead. "I thought, Wow, this is absolutely incredible. It was an amateur play, about a guy who had an accident and got better. I had been having trouble dealing with that and figured it out during the rehearsals.”

An agent attended, and Chris was cast to appear in five episodes of the soap opera Loving.

That creative turn gave him confidence for the even bigger turn that followed.

Chris competing in the '02 Paralympics on a monoski.

After Chris got out of rehab that summer, his coach took him to New Zealand to try out for the U.S. Paralympic alpine skiing team. With no legs, Chris would compete on a monoski, a sophisticated piece of equipment invented in the 1950s that has a single ski, along with the same boots, bindings, and poles as non-disabled skiers use, but the athlete is seated. The sport is called sit-skiing.

“I was just awful that first day,” Chris said. “The head coach was looking at me like, The guy can’t even make it a hundred yards. But early that week, when I made my first real curve turn on the monoski, that was the breakthrough I needed.”

Chris was invited onto the team. At the 1992 Paralympic Winter Games in France, he won two silver medals. At the ’94 games in Norway, he won four gold medals. In the next two games, he won another gold, three more silvers, and two bronzes. At this point, he was the most decorated monoskier in American history.

But Chris was not done yet. He represented the United States at three Summer Paralympic Games, winning a silver medal in racing and setting a world record.

In 2019, he was inducted into the Paralympic Hall of Fame.

But now what?

When Chris’s skiing career ended at thirty-four, he again thought his life was over. He told me that retiring from competitive skiing was “far more difficult” than breaking his back. “I had no idea who I was, and I felt betrayed by my passion. It just dropped me off a cliff.”

So he decided to climb another cliff. He hatched a dream to become the first disabled person to summit Mount Kilimanjaro, the tallest mountain in Africa. Since he couldn’t use his legs, though, Chris would need to scale all 19,341 feet by pedaling a four-wheel mountain bicycle using only his arms. He raised money, built a special vehicle, and recruited an international team to assist him by securing him to a wench, laying down boards, and helping him navigate the boulders, altitude, and stress. At forty-one years old, he set off.

Chris Waddell, the first paraplegic to summit Mt. Kilimanjaro (almost entirely unassisted) on a hand cycle.

The seven-day climb was brutal. At times he moved only a foot a minute. International media were rapt by his heroism.

But then, a mere hundred feet from the summit, the boulders became too large, the wheels of his vehicle too meager, the path unpassable. He had to abandon his dream.

“I was crushed,” he said. “I could see the top. My sole job was to get there. It was not about one man gets broken and overcomes anything. To me, that’s a ridiculous cliché. It was about promising that I would do this. It was about so many people having sacrificed to give me that opportunity, and now I’ve just failed everybody.”

His partners persuaded Chris to let them carry him the final inches to the summit, where he posed for pictures and listened to the local guides sing celebratory songs in Swahili, all while he felt fraudulent and guilty.

Chris at the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro

“And it wasn’t until much later, when I started telling the story to school kids, that I realized the lesson was there all along. Nobody climbs a mountain alone. That was the thing I had to discover: the value of the team. Because for me to say I climbed it myself was complete fantasy. Making it to the top on my own would have perpetuated a lot of what I was trying to eliminate: the sense that people with disabilities need to be apart. We don’t. We need other people. That’s why I talk about that day as a gift. It taught me what I most needed to learn: that I’m just like everybody else.”

It taught him a lesson we all need to learn: the value of rewriting our life stories in the face of setbacks to give them a heroic ending.

☀

Thanks for reading The Nonlinear Life. Please help us grow the community by subscribing, sharing, and commenting below. Also, you can learn more about me, read my introductory post, or scroll through my other posts.

You might enjoy reading these posts:

The Banned Book That Every Child Should Read

ESPN Asked Me to Give Tom Brady Advice About Life After Football. Here’s What I Said.

Rare Snowfall Blankets Jerusalem: 10 Photos of a Divided City United by Joy

Or these books: Life Is in the Transitions, The Secrets of Happy Families, and Council of Dads.

Or, you can contact me directly.