The #1 Thing Parents Are Worried About (And the Most Surprising Thing They’re Not)

How the Pandemic Changed Families Forever

A few years ago, I interviewed Alain de Botton, the wry British author of such modern classics as How Proust Can Change Your Life and On Love. He’s also the author of one of the most popular New York Times opinion essays, “Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person.”

At the time, I was writing a New York Times column about the role of friends in times of crisis. On cue, de Botton gave me one of his patented glum-but-upbeat takes. “Friends should entertain the darkest scenarios and show you that these would, nevertheless, be survivable,” he said. Instead of having my friends placate me with false optimism, he added, “I need grim, grim realism, combined with stoic fortitude — colored by a touch of gallows humor.”

De Botton separately authored one of my favorite descriptions ever about publishing. “Writing a book is like telling a joke and having to wait three years to find out if it’s funny.”

That line came back to me this week as I read a startling new study about parenting from the folks at Pew. In this case, the thing that took three years to pan out was not a joke at all; it was the pandemic.

In the six years I’ve been collecting and analyzing life stories—talking to people about how they navigate transitions in life and work—the signature piece of data I collected is that life transitions take, on average, five years. When people first experience a shakeup—what I call a lifequake—this news can feel daunting. Wait, I’m not going to be through this upheaval for half a decade?!

But three years into the pandemic, I think we all have a better understanding of how this timeline works: Many of us are just getting around to following through on a life change that the pandemic shook loose from our routines. Since the start of this year, I’ve talked to folks who are leaving their spouses, having affairs, quitting jobs, starting companies, going on pilgrimages, and taking sabbaticals. Most of these steps, I would argue, are part of the messy middle of the massive, collective lifequake of COVID-19. It’s as if we were all pumped up on adrenalin the last few years and now that we’re through (what appears to be) the worst of it, all sorts of delayed responses are coming to the fore.

Perhaps no part of our lives better reflects this turmoil than our families.

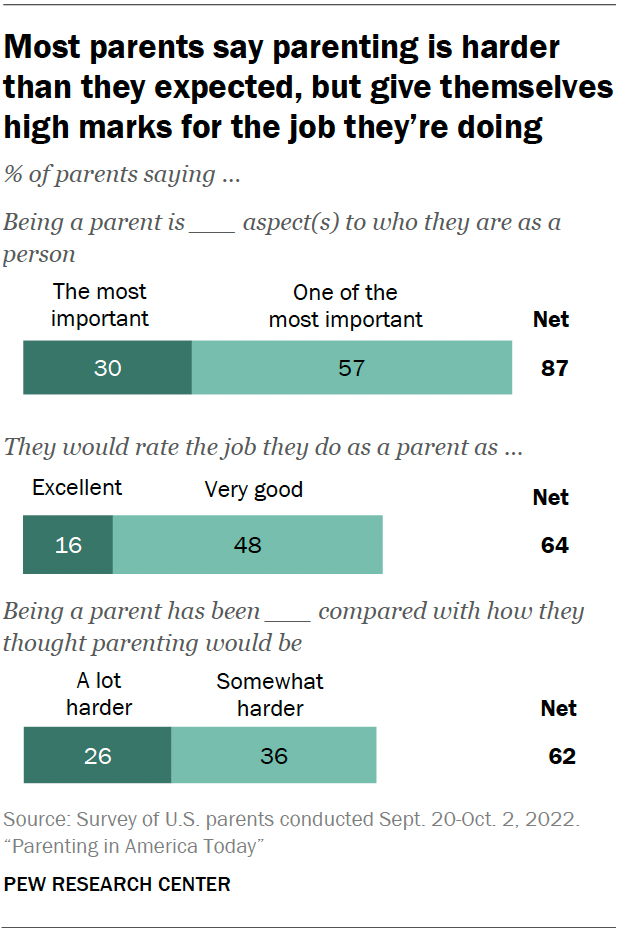

Last month, Pew Research Center released a massive study of 3,757 U.S. parents with children under 18 called “Parenting in America Today.” The overall tenor of the report is how difficult most parents find the experience of having children. More than four in ten parents say that being a parent is tiring, and 29 percent say that parenting is stressful all or most of the time. Nearly two-thirds of parents say that raising children has been at least somewhat harder than they expected, with about a quarter (26 percent) saying it’s been a lot harder.

But the biggest headline in the report is that the pandemic has changed what parents worry about. Here’s how Pew researchers Rachel Minkin and Juliana Menasce Horowitz summed up the finding:

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and amid reports of a growing youth mental health crisis, four-in-ten U.S. parents with children younger than 18 say they are extremely or very worried that their children might struggle with anxiety or depression at some point. In fact, mental health concerns top the list of parental worries.

By contrast, some of the more longstanding parental worries, including “having problems with drugs and alcohol” and “getting pregnant/getting someone pregnant,” are much further down the list. On the bottom of the overall tally of parental fears, mentioned by only 14 percent of all parents, was “getting in trouble with the police.” This figure, however, was understandably higher among Black and Hispanic parents than their White and Asian counterparts.

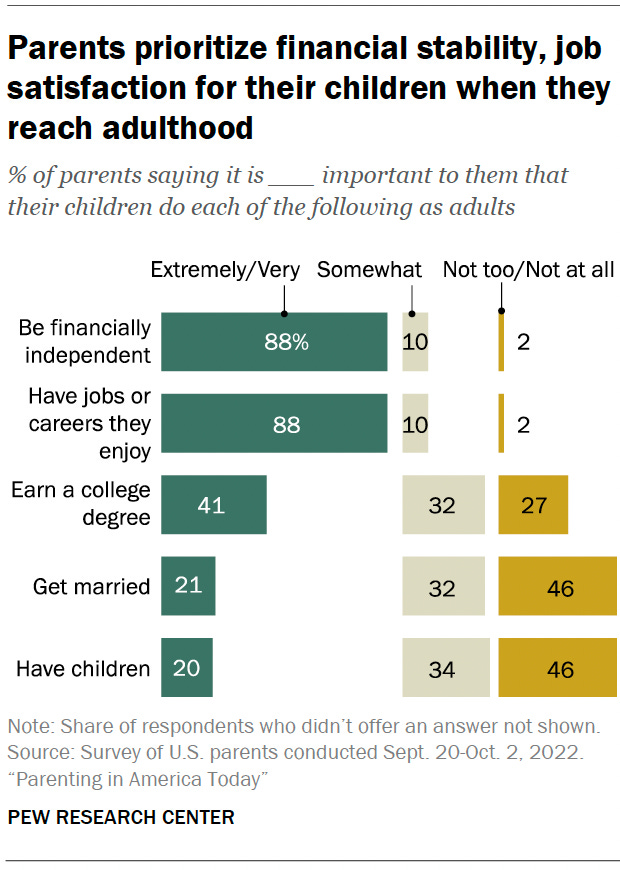

The new weight parents put on mental health also seems to be weighing on the priorities parents hold for their children. When asked what aspirations they hold for their children as adults, parents far and away prioritize financial independence and satisfaction at work. Roughly nine-in-ten parents say that it’s extremely or very important to them that their children be financially independent when they are adults; the same percentage say that it’s equally important that their children have jobs or careers that they enjoy.

As someone who’s written a new book, The Search, about finding meaningful work, I’m thrilled by this news. And if you know someone in their 20s (or 30s, or 40s, or older) who is looking for a road map for being financially independent and having work they enjoy, I hope you’ll consider recommending my book to them!

But, as hopeful as this turn toward meaningful work is, the report that drops a statistic so shocking that Ross Douthat in the NYT says he initially didn’t believe it could be true.

Only 21 percent of parents say that they prioritize their children getting married, and only 20 percent say they prioritize their children having children themselves. Even more surprising: fathers want their children to get married and have children even more than mothers. As Pew summarizes the result: “Fathers are more likely than mothers to say it’s extremely or very important to them that their children get married (25 percent vs. 18 percent of moms) and have children (24 percent vs. 17 percent).”

I find these figures breathtaking: Only one in five parents prioritizes becoming a grandparent. RIP to centuries of jokes involving parents pressuring their children to bring them babies. No wonder parents don’t want weddings anymore; they won’t have anything to discuss!

But jokes aside, the consequences of this finding are profound. Even if you factor in a little exaggeration in these numbers, parents’ priorities are clearly shifting. Happiness is defined more by work these days than by family. If given a choice between having children find meaningful work or meaningful relationships, parents by four to one prefer the former.

In the battle between work and family, work has clearly won. The truth is, the ramifications of this change are just beginning to be felt and we’ll be sorting through the consequences of this change for generations. In fact, one might even say, that for society, making a shift this profound is like telling a joke and waiting 30 years to find out if it’s funny.

This shift is caused by of the lack of social supports for parents and caregivers. There is almost no help that parents get for being parents - mothers get lower wages, fathers get wage bumps and are expected to work more. Caregivers are poorly paid.

Failing to have a category for meaningful relationships or community strikes me as a profound limitation to the statistic. The question forces a skew between having a bio family or traditional family and working. So many of us (parents) have friendships or a life outside of work.